Shed Damp: The Hidden Patterns I Discovered by Monitoring My Shed Every 5 Minutes for a Week

Introduction - 'Why I Decided to Monitor My Own Shed'

There's a moment every shed owner has when they look around at their tools, bikes or storage boxes and think, 'Is my shed actually damp... or am I just imagining it?'

Is the inside of my shed damp?

look at some different shed roof designs

Is the inside of my shed damp?

look at some different shed roof designs

I've had that moment many times, usually when I notice a light bloom of corrosion on one of my bikes. I've always accepted that 'a bit of rust in a shed is inevitable,' but recently I started wondering whether that was really true - or whether something in the shed's daily environment was quietly encouraging it.

After years of helping people deal with condensation, rusty tools, swollen MDF, wrinkled paper, and collapsing cardboard boxes, it struck me that I was still relying on instinct in my own shed. For all my experience, I'd never actually measured what was happening inside it.

So, during a cold week in late November, I decided to stop guessing.

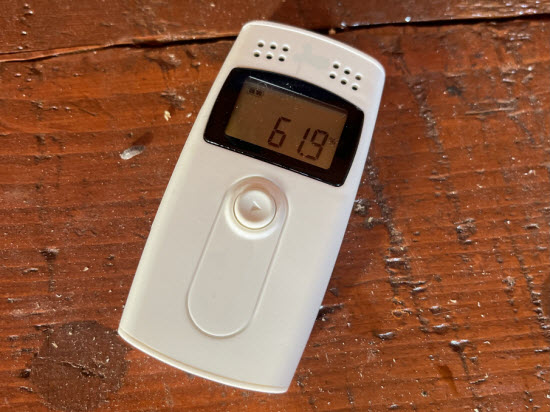

I placed a small temperature-and-humidity recorder on the bench which is at the back of my 3 x 4 m shed. Nothing exotic - just a reliable little device that would quietly get on with the job. I set it to take readings every five minutes, day and night, for over a week.

The recorder was placed on a bench at the rear of the shed out of direct sunlight

The recorder was placed on a bench at the rear of the shed out of direct sunlight

This simple unit records the temperature and humidity every 5 minutes

This simple unit records the temperature and humidity every 5 minutes

My goal was simple: to understand the real, everyday moisture behaviour of a typical UK shed.

- I wanted to see the daily cycle

- I wanted to understand how cold nights and mild afternoons actually changed things

- And I wanted to find out whether my bikes - and everything else in the shed - were living in conditions that encouraged corrosion

The results weren't dramatic, but they were revealing. They showed that even a shed that feels dry can have a hidden moisture rhythm running just beneath the surface.

The First Surprise - My Shed Is Drier Than I Expected (But Only Just)

When the first batch of data came in, I'll admit I was ready for trouble. It had been a cold stretch of weather, the sort of week where you half-expect to find beads of moisture forming on metal surfaces. But the initial readings told a different story.

- The air temperature inside the shed never dipped below the dew point - not once

- There were no full-condensation events

- But the dew-point gap - the margin that prevents condensation - was often extremely small

On several nights, the shed floated just a degree or two above the dew point. That's close. Closer than I ever would have guessed.

Even when the air stays above the dew point, many of the objects inside the shed don't.

Metal cools faster than air. Tools, screws, bike chains, saw blades - all of them can sit colder than the surrounding air, meaning they may dip below dew point even when the air hasn't. So a shed can be 'safe on paper' yet still quietly nibble away at tools and equipment.

The Hidden Daily Pattern - Warm Afternoons, Damp Mornings

Once I had a few days of data, a very clear rhythm began to appear - a kind of breathing pattern the shed repeated every 24 hours.

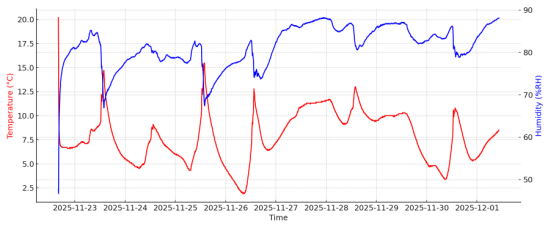

The graph of temperature (red) and relative humidity (blue) over 8 days

The graph of temperature (red) and relative humidity (blue) over 8 days

- Overnight: temperatures dropped and humidity rose

- Morning: the shed warmed slowly and humidity began to fall

- Afternoon: the shed reached its driest point

- Evening: temperatures fell again and humidity climbed

This cycle repeated almost perfectly day after day.

If you looked at any single moment, you'd think the shed was fine. But when you see the full curve across several days, you realise the shed is constantly moving between its driest and dampest states - and its most vulnerable period is always the early hours of the morning.

The Cycling Spike - How One Hour of Exercise Lifted Humidity

A few days into the experiment, an unusual lift in humidity jumped off the graph. It was sharp, flat-topped, and didn't match the gentle overnight rise or morning fall. It happened twice: on 23rd November and 25th November, both between 6 and 9 am.

- Humidity surged to 82-83% RH

- Temperature barely moved

- The spike lasted almost an hour

And then I remembered: I was riding my bike in the shed at that exact time.

This wasn't weather. This wasn't a structural quirk. This was human-generated moisture.

A single hour of cycling can release around 100 ml of moisture into the air through increased breathing and perspiration. In a small, relatively airtight shed, the effect is instant.

This matters hugely for:

- Garden offices

- Hobby sheds

- Workshops

- Indoor exercise spaces

If one person can push humidity close to 83% in under an hour, imagine two people - or several hours of working, breathing, soldering, sanding or painting.

Why People Cause More Shed Damp Than Weather Does

Once the cycling spike made sense, everything else became clearer: people add more moisture to a shed than nearly all weather conditions do.

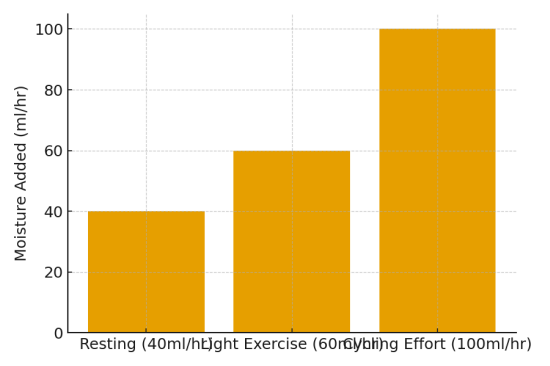

Approximate moisture output per hour:

The amount of moisture added to the atmosphere varies with activity

The amount of moisture added to the atmosphere varies with activity

- Resting: ~40 ml/hour

- Light activity: ~60 ml/hour

- Cycling / harder breathing: ~100 ml/hour

And the reason it shows up so dramatically is simple: a shed has low air volume and minimal ventilation.

In a house, you don't notice this. But in a shed, moisture builds up fast. Door closed + human breathing = rising humidity.

This is why garden offices and hobby sheds often develop mustiness, rusting tools, or damp paperwork even when the building itself is perfectly sound.

The Real Risk - Cold Metal, Not the Shed Air

One of the most important insights from the experiment was that risk doesn't just come from the air condensing.

It comes from the objects inside the shed hitting dew point before the air does.

Metal cools fast and holds the chill. That means:

- Tools

- Screws

- Cast-iron components

- Bike chains

- Saw plates

- Window latches

- Roofing screws

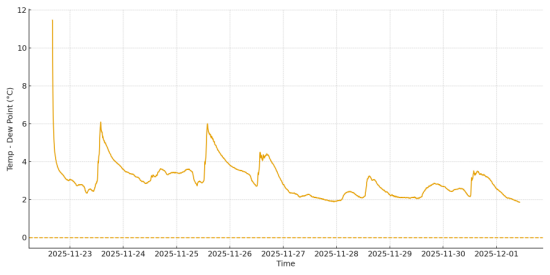

This graph shows the dew point in the shed. The air never actually reached the dew point. However material in the shed is at risk when the dew point

is is within 2 degrees of it, as the air changes temperature more quickly than solid materials.

This graph shows the dew point in the shed. The air never actually reached the dew point. However material in the shed is at risk when the dew point

is is within 2 degrees of it, as the air changes temperature more quickly than solid materials.

...can all drop below the dew point even when the air is still above it.

And it isn't only metal.

Paper and cardboard are equally vulnerable:

- They absorb moisture directly from the air

- Paper wrinkles and warps

- Books develop wavy pages

- Cardboard boxes soften, sag or collapse

- Packaging loses structural strength

You don't need visible condensation for damage to occur. You just need humidity high enough for long enough.

What Measurement Teaches Us - and Why Guessing Fails

By the end of the week, one lesson stood above everything else:

You can't manage what you don't measure.

Before this experiment, I would never have known:

- The shed spends much of each night in the high-risk humidity zone

- My morning cycling sessions were causing sudden 10% humidity spikes

- The shed warms slowly, leaving cold surfaces risky for longer

- The dew-point margin is often only 1-2°C

- The shed becomes most dangerous at 6-9 am, not during the day

A shed can look perfectly dry at noon and still be quietly damaging your belongings at dawn.

Measurement replaces guesswork with reality. And once you see the real pattern, you can make real improvements.

What I'll Test Next - Insulation, Ventilation, Heating & Dehumidification

This first week wasn't the end - it was the beginning.

Now that I understand my shed's natural moisture cycle, I want to see what happens when I change things. Over the next phase of the ShedSense project, I'll be testing:

- Insulation - how much does it reduce nightly cooling and morning dampness?

- Ventilation - what's the effect of adding a controlled fan or bilge blower?

- Heating - can a gentle, low-watt heater stabilise humidity safely?

- Dehumidification - how well do desiccant units work in a cold shed?

Each test will be monitored the same way: every five minutes, day and night, with graphs to show the results.

This little experiment revealed the hidden rhythms of my shed - and I'm looking forward to sharing the next set of discoveries.

Moisture Resources

- Shed Moisture Control - How to understand the overall moisture behaviour inside your shed

- Stop Shed Condensation - Practical steps to prevent condensation in your shed once you spot the warning signs

- Shed Dehumidifier vs Heater - How to decide whether heat or moisture removal is the better fix in your shed

- Ventilating a Shed- Why airflow matters as much as temperature in a small shed

- Why Metal Roofs Sweat - Understanding why cold roof surfaces can condense long before the shed air does

- Is Bubble Wrap Insulation Making Your Shed Damp? - Why some insulation types make damp worse, not better

Keep in touch with our monthly newsletter

Shed Building Monthly